I never went to Dixmont, though lots of my high school classmates and friends did. My parents mildly discouraged me from venturing up into the thickly wooded hills where it sat, not because kids went there to drink and smoke and scare each other (which they did) but because the dilapidated buildings were full of friable asbestos and the underground tunnels were probably even more structurally unsound than the buildings. The property, at the time I was a teenager, had been essentially abandoned for more than a decade.

Dixmont was named after Dorothea Dix, the nurse and reformer whose lobbying efforts were instrumental in creating the asylum system in the United States. The asylum movement, originating in the 1840s, aimed to improve the treatment of people with mental illnesses, who were typically subject to a litany of esoteric forms of abuse and neglect including, but not limited to, exorcism, bloodletting, and warehousing in jails. Dix, who worked in a jail as an English teacher, was shocked by […]

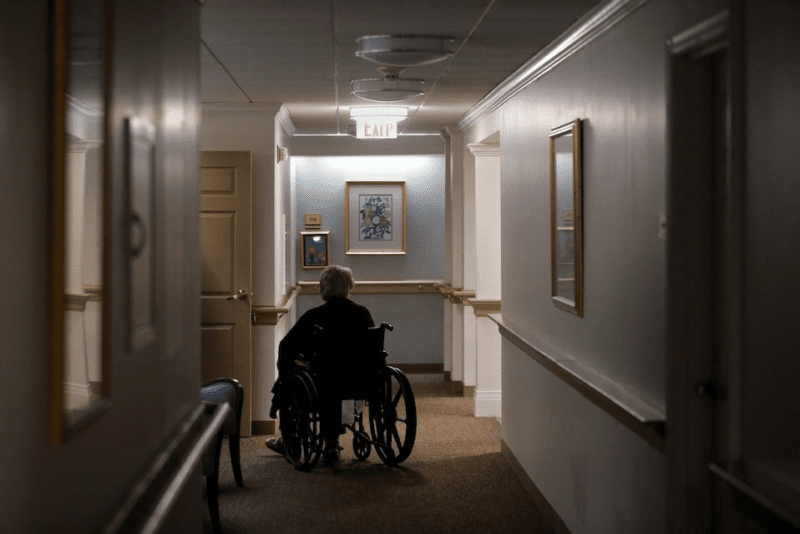

This discribes, but is not similar to the nursing home where my mother died. They dio not even watch over her, even though the cost to be there was $11,500

per month. The last time I saw my mother, she had bruises all over her body from falling or bumping into things. For the price, they should have had a person looking over her 24 hours a day!

As the article states: “As Adler-Bolton and Vierkant argue, and many have said—in the world post-2020, we are all surplus.” This has profound implications, especially with the advent of AI driven tools such as ChatGPT which will put many, many workers of out jobs. The truth is quickly coming that the elites will not need many of us, and we will become surplus. This reality has not truly sunk in, and will be here in the next 12-24 months. The only saving factor will be the massive energy needs these systems will require to operate, and that will be a hard constraint.